Den här artikeln är kopierad och återpublicerad från The Barents Observer, med tillstånd av redaktör Thomas Nilsen. I februari 2019 blockerades The Barents Observer för ryska läsare, efter att tidningen publicerat reportaget om Dan Eriksson i rysk översättning.

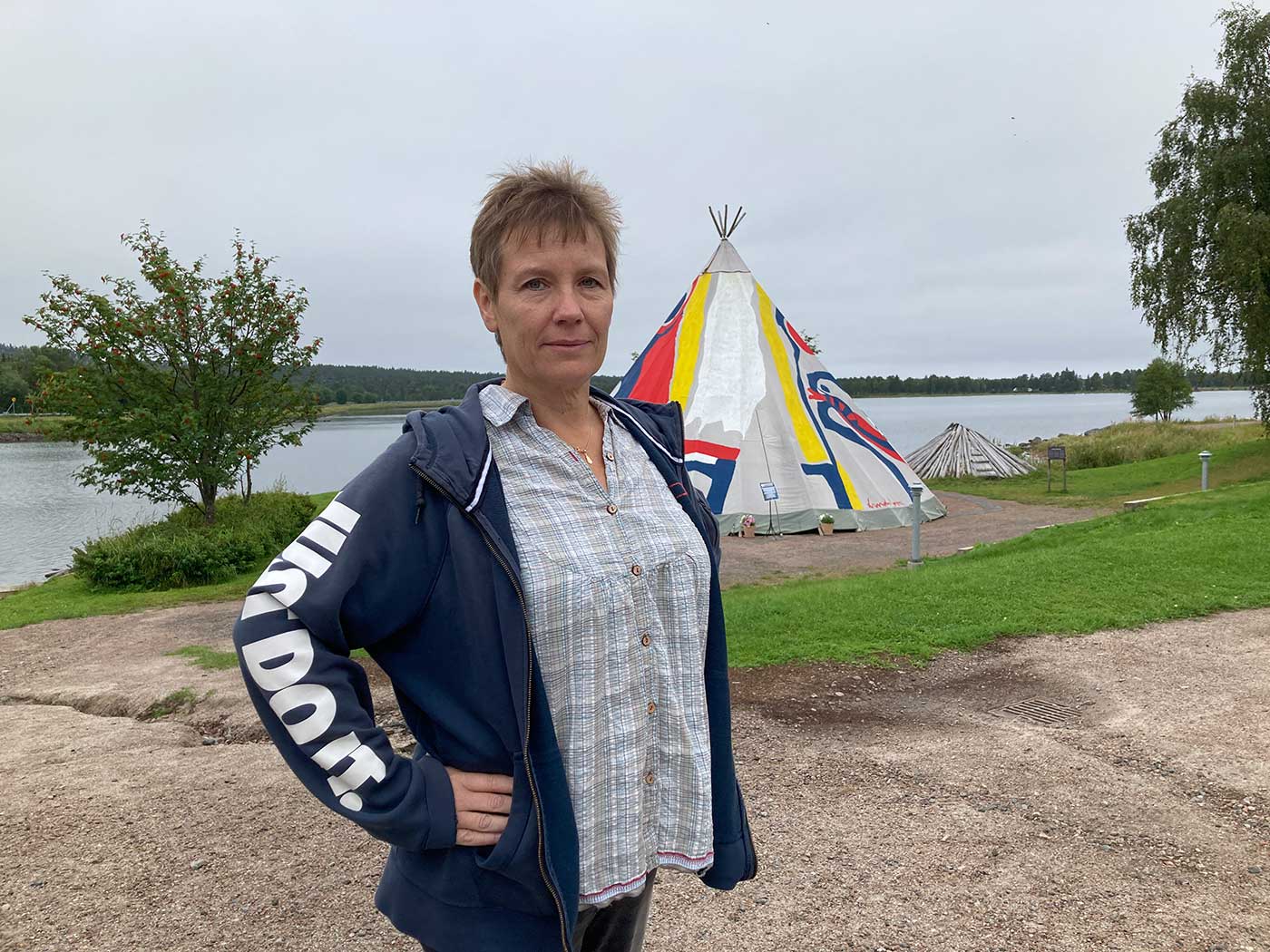

Marianne Hofman is publisher of the small local news online Arjeplognytt in northern Sweden. Photo: Peder Lundkvist

Journalist and publisher Marianne Hofman refuses to depublish the article despite being threatened by Russia’s censorship agency. “Instead I will place it on the front page again so everyone can see what Russian authorities want to hide,” she states.

It was in December 2018 that journalist Marianne Hofman made an interview with Dan Eriksson, a proud gay Sámi from neighboring town Arvidsjaur.

The interview was published in her own news online Arjeplognytt, but also by Samefolket, a journal with dedicated news articles for the Sámi people of northern Sweden. A few weeks later, the Barents Observer published an English and Russian version of the interview.

It took two suicide attempts before Dan Eriksson began to live as the one he is. After years of denial and mental health problems, he now feels happy and wants to help others understand how important it is to dare to be oneself. Photo: Peder Lundkvist

The story is about Dan Eriksson, which is not for Russians to read according to the repressive authorities in Moscow. For Marianne Hofman, though, such stories are important for everyone, whether the readers are in a small Sámi community or in bigger cities like Stockholm or Moscow.

Dan Eriksson talks about how he for years struggled to overcome taboo and prejudice connected with his homosexuality. He was deeply depressed and twice tried to commit suicide.

The article contains information “prohibited for public distribution in the Russian Federation” states the formal letter Marianne Hofman received from the state media watchdog Roskomnadzor.

Mentioning suicide attempts, however, Dan Eriksson today helps others overcome their mental challenges. The Roskomnadzor notice points to the law stating that any information about ways to commit suicide is illegal.

Hofman got 24 hours to restrict access (remove) to the article. If not, Russian authorities will block the news online for access from within the country.

“Of course, I’m not going to unpublish the story,” says Marianne Hofman. “Given the attention to this case again, I will instead place it on the front page.”

The Russian language version of the interview was in February 2019 the formal reason why Roskomnadzor decided to block access to the Barents Observer for readers inside Russia.

Shortly after the Barents Observer was blocked, both Arjeplognytt and Samefolket republished the Russian version of Dan Eriksson’s life story.

“We should not be silenced,” Hofman makes clear. “Those were the exact words by Dan Eriksson himself in the article where he told about his challenges,” she says.

“When the Barents Observer received a similar letter from Roskomnadzor three years ago, with a demand to depublish the article, it was obvious to me to publish the Russian version of the interview with Dan Eriksson, even though Russian readers are not my main target group,” Marianne Hofman tells.

She underlines that it is “totally unacceptable” that any authorities, in this case the Russian, are trying to influence the content in an independent media.

“Arjeplognytt is my newspaper. I own it and run it. I’m the chief editor and publisher. It is for me, not others, to take the responsibility and decisions for the content,” Marianne Hofman says.

Russian authorities have blocked or deleted some 138,000 websites since Moscow launched its invasion of neighboring Ukraine in February, the country’s prosecutor general said earlier in August.

All of Russia’s independent media has either been blocked or shut down since February, with many journalists fleeing the country to escape prosecution.

Russian authorities have also outlawed Facebook and Instagram as “extremist” organizations since the war began and restricted access to Twitter.

Ovanstående reportage är kopierat från The Barents Observer och med tillstånd återpublicerat i Arjeplognytt.

Länk till reportaget om Dan Eriksson, publicerat i Arjeplognytt, finns här.